Whether or not a plaintiff can recover damages after an accident usually comes down to whether the defendant was negligent

Negligence is one of the most common personal injury causes of action. The term is so common that people often throw it around without fully understanding what it means.

Let’s take a close look at negligence, gross negligence, negligence per se, and contributory and comparative negligence.

What is the tort of negligence?

The majority of accidents happen because someone is careless. If this carelessness falls below a legally recognized standard, the person’s conduct is considered “negligent” and the person is liable for any damages caused by their negligent conduct.

To put it another way, negligence is the failure to exercise the appropriate level of care.

Common examples of negligence include:

- A driver who runs a red light

- A driver who texts while driving

- A store owner who fails to clean up a spilled drink in a timely manner

- A doctor who operates on the wrong part of a patient’s body

How do I prove negligence?

To prove negligence, the plaintiff (the injured party) must establish 3 elements:

- Duty. The plaintiff must prove that the defendant owed them a duty of care. A duty of care arises when the law recognizes a relationship between the plaintiff and defendant requiring the defendant to exercise a certain standard of care to avoid harming the plaintiff.

- Breach. The plaintiff must prove that the defendant breached the duty of care. A breach occurs when the defendant fails to meet the standard of care required.

- Causation. The plaintiff must prove that their injury was caused by the defendant’s breach of the standard of care.

Let’s take a closer look at each of these 3 elements:

1. Establishing a duty of care

In most situations, the law imposes a duty on people to act with “reasonable care” (sometimes called “due care”) while performing acts that could foreseeably harm others.

What is reasonable care?

Reasonable care is the level of care that a “reasonably prudent person” would exercise in the same or similar situation.

In some cases, however, the standard of care owed is more specific than the general duty to exercise reasonable care. For example, in some states, premises liability laws dictate that property owners owe visitors certain specific duties (such as searching for dangerous conditions before the guest arrives).

In other cases, the standard of care owed is higher than the standard of reasonable care. For example, common carriers (those who transport people or property for money) typically have a duty to exercise the “highest degree of care” as opposed to a “reasonable degree of care.”

Here are some examples of different types of individuals and the duty of care they owe in most states:

| Party | Standard of reasonable care |

|---|---|

| Drivers | Duty to exercise reasonable care to avoid harming other people on the road |

| Store owners | Duty to exercise reasonable care in the maintenance of business premises, including keeping the premises free of dangerous conditions |

| Medical professionals | Duty to exercise the degree of skill and care expected of a reasonable health care provider in the same profession with the same training and experience |

| Product manufacturers | Duty to sell products that are free from defects |

| Bus drivers and other common carriers | Duty to exercise the highest degree of care to secure the safety of passengers |

2. Establishing a breach

Once the plaintiff establishes the standard of care that the defendant owed them, they must then prove that the defendant breached the standard of care.

There is no formula for determining whether a defendant breached the applicable standard of care; the question is one decided by a judge or jury.

Attorneys often frame the question as one of foreseeability. In other words:

Would an ordinary person in the defendant’s position have anticipated that their conduct could have caused the harm that ultimately resulted?

If so, the conduct was negligent.

In the case of professionals (especially those in specialized fields, such as doctors and structural engineers), experts are typically brought in to testify as to the industry norms and whether the professional’s conduct fell within those norms. In fact, many courts require expert testimony in these situations.

3. Establishing causation

Before the court will hold the defendant liable, the plaintiff needs to establish that the defendant’s carelessness caused the plaintiff’s injury.

One way to think about causation is to ask the following question:

Would the harm have occurred if the defendant hadn't acted in the way they did?

If the answer is NO, then the action caused the harm.

Causation seems simple enough on the surface, but it can get complicated when experts disagree about whether A can cause B (such as in a product liability case in which the plaintiff alleges that a certain chemical caused their cancer).

The other tricky part about causation is that the plaintiff must tie the defendant’s negligent conduct (not just their conduct) to the harm.

Consider the following example:

In this example, it’s not enough to prove that Linda hit Carlos with her car, or even that Linda was driving negligently. Rather, Carlos must prove that it was Linda’s excess speed (her negligence) that caused his harm.

If it can be shown that Carlos would have been hit by the car even if Linda was driving the speed limit, then the accident was caused only by Linda’s conduct, not by her negligent conduct, meaning Carlos can’t recover damages.

What is gross negligence?

In most states, punitive damages are only available in personal injury cases if the defendant acted with “gross negligence.”

So what is gross negligence and how does it differ from ordinary negligence?

Courts defined gross negligence differently, but all agree that gross negligence is something more egregious than ordinary negligence.

“Gross negligence represents an extreme departure from the standards of ordinary care to the extent that the danger was either known to the defendant or so obvious that the defendant must have been aware of it.” -Saltz v. First Frontier, L.P., 782 F. Supp. 2d 61, 75 (S.D.N.Y. 2010)

Examples of actions that would probably be considered grossly negligent in most states include:

- A doctor operating on the wrong limb

- A nursing home that failed to provide food

- A store owner failing to fix a broken porch step despite watching several customers fall

- A driver speeding in an area with heavy pedestrian traffic

What is negligence per se?

Under the doctrine of “negligence per se”, the defendant’s law-breaking act serves to establish the first 2 elements of negligence (duty and breach) automatically. In other words, if a plaintiff can show that the defendant broke the law, the plaintiff doesn’t have to show that the defendant owed you a duty and breached that duty.

In most states, negligence per se only applies in situations where the defendant breaks a law that:

- Was enacted for the protection and safety of the public, and

- Expresses the rules of conduct in specific and concrete terms.

For example, drunk driving cases in which the driver was operating a vehicle above the legal limit often fall under the rule of negligence per se.

What is contributory and comparative negligence in a personal injury case?

In some cases, the plaintiff is partially at fault for their accident.

Consider the following example:

In this example, a court could reasonably find that both Jason (the defendant) and Phillip (the plaintiff) are partially responsible for the accident.

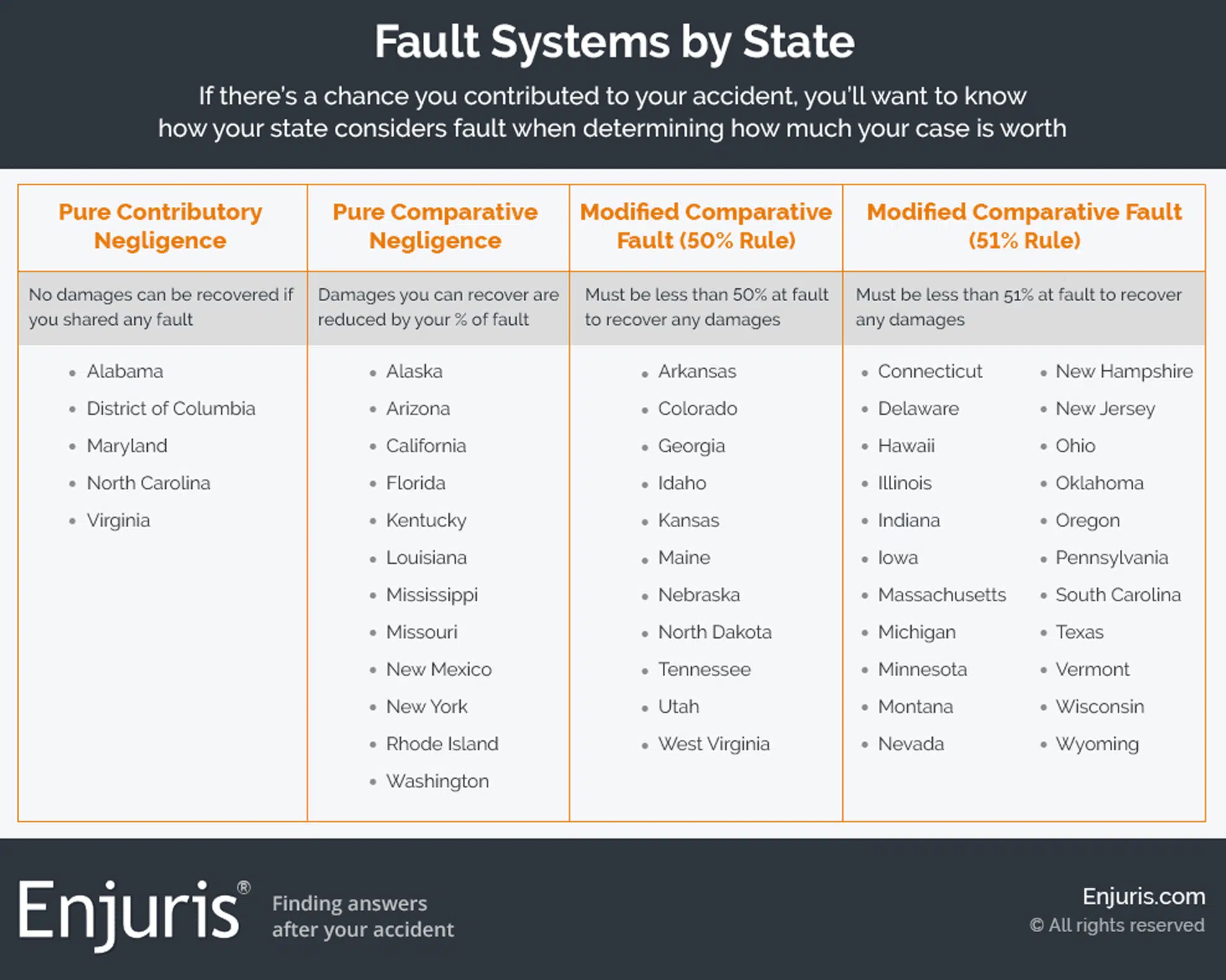

When a plaintiff is partially responsible for their accident, the court must determine how the partial fault impacts their ability to recover damages. Each state has adopted 1 of 4 rules to make this determination:

Do you think someone’s negligence caused your accident? Use our free online legal directory to schedule an initial consultation with an attorney near you today.

Connect to top-rated lawyers in seconds using our comprehensive national directory

See our guide Choosing a personal injury attorney.